In Tate St Ives

- Artist

- Christopher Wood 1901–1930

- Medium

- Oil paint on board

- Dimensions

- Support: 794 × 1086 mm

frame: 917 × 1215 × 91 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by Mrs Lucy Carrington Wertheim 1962

- Reference

- T00489

Display caption

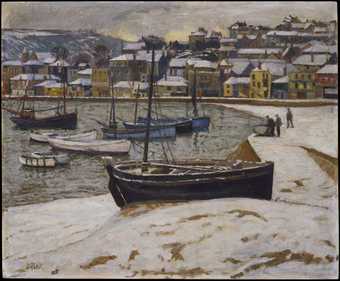

Though in Brittany, this scene is similar to many works painted by Wood in Cornwall. Towards the end of his short life, Wood spent periods working in both places in pursuit of a ‘naïve’ style of painting. In 1928 he visited Cornwall with his friends Ben and Winifred Nicholson. In St Ives the two men came across Alfred Wallis, whose ‘primitive’, child-like paintings made a deep impression on their subsequent work. For them, adopting Wallis’s instinctive style allowed them to reject the artificiality of established painting for a more authentic mode of expression.

Gallery label, July 2007

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Christopher Wood (1900-30)

Boat in Harbour, Brittany 1929

Oil on board 794 x 1086 (31 1/4 x 42 3/4)

Inscribed on back in various hands: in pencil 'WERTHEIM GALLERY | 3/5 Burlington Gardens W.I. | Boat-Harbour | C. Wood' r.; in blue pencil 'To Mrs WERTHEIM' and stencilled '659 MH' on top stretcher member; in white chalk 'No 7[?8] BAKEWELL' on left stretcher member; in blue paint 'WERTHEIM' on central stretcher member

Presented by Mrs Lucy Carrington Wertheim 1962

Boat in Harbour, Brittany

was painted on a relatively large piece of poor quality millboard of the type favoured by Wood when away from his studio. The white oil ground was applied in a single thick layer with a household brush, a practice common to the artist's other paintings on board, including Church at Treboul

and Douarnenez, Brittany

(q.v.). This is consistent with the commercial primer called Coverine, which Wood had recommended to the Nicholsons in the previous year for covering rejected compositions. The condition of Boat in Harbour

suggests that the board was prepared by the artist himself, as the ground was applied over a label which remains visible where the rigging meets the main mast; its cursive inscription, '[?Leay]', remains partially legible though unintelligible. An attempt was made to strengthen the board after completion by tacking it to a pine stretcher; as a consequence of this arrangement, the layers of millboard have required consolidation at the edges and the tacks, which are visible along all sides, have had to be treated for rust. The brushstrokes of the ground provided a rough texture for the painting, which was washed and brushed in a thin layer over the preliminary pencil drawing. The white ground remains exposed in the sky, while in other areas, such as the gunwales, a little paint has been rubbed into the surface. The painter's casual technique is evident in the partially scratched-out figures on the quayside to the left. The use of scratching to lighten the surface and to reveal the layer below was one shared with Ben and Winifred Nicholson. Here it exposes pencil underdrawing; although the bonnets of the women have been repainted, the upper parts of their bodies have been left unresolved.

Close observation of the surface indicates that the boat itself was painted first. The inky sea was scumbled into the textured ground around the boat, but before the drawing of the rigging for the furled sail to the right. The main burnt-red sail has been considerably adjusted. At first it billowed to the right in a curve that is still visible in the adjustments then made to the sea and the pier. The present position of the yardarm and the pushing sailor make the sail curve away more forcefully from the observer. This is associated with the ambiguous relationship of the boat and the port. The inward movement of the boat indicated by the sails appears to be contradicted by the tautness of the anchor chain and the slack rope to the dinghy. The port itself was sketched in pencil but was only painted after the boat. This is especially noticeable in the thick working of the quay wall around the succinct handling of the foremast and sail. The evident speed of execution, facilitated by a reliance on familiar subject matter, suggests that Boat in Harbour

may have been completed in one day, a practice of which the painter wrote in the following summer (letter to Mrs Wood, 1 July 1930, TGA 773.10).

Sailing boats were a passion for Wood, and he painted them throughout his short career. They were characteristically the central focus of the composition and seen in broadside, a view which favoured the display of the activities of the crew and the detail of the rigging and equipment. Leaving Port, 1927 (private collection; repr., Axis, 7, Autumn 1936, p.7), bought by Lord Berners, helped to establish this format. The ship itself is painted in the smooth static style of the period, and Wood considered it one of his most successful (letter to Mrs Wood, 7 Sept.1927, TGA 773.7). Because of its greater size but compositional similarity Boat in Harbour

may be considered the culmination of the ship paintings made during the spring of 1929, such as The Quay, Dieppe, 1929 (Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums, repr. Ingelby 1994, pl.25). By the following year, he signalled the frequency of the subject in writing, 'I have painted a good deal of architecture and less boats for a change and this seems to make it easier to make a quieter composition'. (letter to Winifred Nicholson, ? July 1930, TGA 8618.1.3.)

Boat in Harbour

was probably painted during Wood's first trip to Brittany in the summer of 1929, when he visited Dinard, and then stayed at the twin ports of Douarnenez and Treboul. By 30 July he was in Douarnenez but, by his own admission, it took him some time to get down to work. On 15 August, he wrote to his mother in England:

It is the most charming place with a lovely port and beautiful bathing beach not far away on the right [to] which one walks through cornfields and pine woods, on the left is another little port with lovely boats that go to Spain and Ireland to fish, and then another beautiful beach with nice little hotels and hills and woods and the most lovely country behind. It is more like Devonshire than Cornwall, but much the same.

(TGA 773.9)

His comparison to Cornwall implicitly referred to his mother's Cornish ancestry, and to his extended stay there with the Nicholsons in the previous year. Wood was not entirely isolated in Brittany. He maintained his correspondence with the Nicholsons and others. What is more, the poet Max Jacob (of whom he painted a portrait, now in the Musée de Quimper) and the painter Christian ('B?b?') Berard were staying at the same Douarnenez hotel, and Wood was joined by his mistress, Frosca Munster.

Towards the end of August Wood rented a house across the river at Treboul. It was there that he did most of his painting. His letters confirm boats as his favoured subject, and indicate that his experience of them came on several different levels. Initially, he was an observer of the devout and apparently timeless life of the fishing communities. This picturesque aspect had been exploited since the end of the nineteenth century by academic painters, such as Jules Breton, and avant garde painters, such as Paul Gauguin. Just as they had shown peasants dressed in traditional costume, so Wood placed figures on the quayside in Boat in Harbour

wearing Breton bonnets which signal the location. The casual handling and rich colouring of Wood's paintings may also be seen as lying within the tradition established by Gauguin.

The view of a timeless ruralism found in Brittany was made more immediate for Wood by his sympathy for Alfred Wallis's work, itself primarily of ships. Wood's extended period in St Ives in the previous autumn resulted in a genuine admiration. This had been succinctly expressed when he wrote to Frosca Munster (28 Oct. 1928, TGA 723.20): 'Winifred says that no one has taken the slightest interest in Wallis's things in London, how stupid people are, uncivilised brutes. How do you think I will sell my pictures which are far less good than his.' Wallis painted out of his own experience of the subject, creating a pictorial parallel for the original activity, whether fishing, putting into port or navigating by recognisable headlands. This immediacy had a particular resonance for Wood and he considered the fisherman painter one of his most important teachers. His example was reflected in the loosening of Wood's technique and the greater spontaneity in brushwork which took place between Leaving Port, 1927 and Boat in Harbour. Evidence is also found in the casual nailing of the board of Boat in Harbour

to the stretcher, a practice used by Wallis, and in the detail of the boat itself. Indeed, the closely comparable image of a Penzance boat in harbour, PZ 134, 1930 (Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne, repr. Ingleby 1994, pl.28) confirmed that Wood recognised the fishing boats on both sides of the Channel as representations of the sort of international exchange of which he had written to his mother.

In relation to the subject of Boat in Harbour, it is worth noting that Wood was also an experienced sailor. The delight he had in boats was a recurring theme. In an undated letter to his mother from Treboul, he wrote:

I have a little sailing boat which I adore, I sit in and glide along looking quietly at all the things I love most, I see the lovely fishing boats with their huge brown sails against the dark dark green fir trees and little white houses instead of always against the sea and an insipid sky. We go in our little boat in the evening to Douarnenez dine with some friends, she [Frosca] plays bridge and back we go.

(TGA 773.9, ?Aug. 1929)

His use of this boat around Treboul, Douarnenez and their inshore waters meant that he had to handle it amongst the large fishing vessels built for crossing Biscay.

As with many other images of ships, Wood was careful to include in Boat in Harbour

the identification number, Dz2134, which indicated that this vessel was registered at Douarnenez. It is impossible to ascertain if this identified a real boat as the relevant records are no longer extant in the Archives du Service Historique de la Marine in Brest.

The port entrance in which it is set has been identified by Sophie Barthelemy of the Musee de Quimper (letter to the compiler, 12 March 1996, Tate Gallery files) as Treboul, with the church tower of Saint Joseph introduced at the left. However, as Barthelemy has observed, Wood took liberties with the view in including the church and the foreground quay, and excluding the Ile Tristan.

Despite these modifications, the particularity is persuasive. The efforts of the sailors on board the boat are strenuous and set against the schematic zigzag division of land and sea created around the boat by the harbour wall. The extension of the masts out of the top and right side of the painting means that the structure of the boat determines and dominates the composition. It appears close-up and immediate. However, it is notable that in comparable images of ships Wood introduced mythological and symbolic references associated with Cocteau's 'rappel à l'ordre'. In the contemporary Le Phare

(1929, Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge; repr. Ingleby 1994, pl.47) a red-sailed ship is juxtaposed with playing cards and the newspaper of the title to evoke a sense of fatality.

By early September 1929 Wood had exhausted both his creative and his financial resources in Brittany, but he was satisfied with his output. He wrote to his mother on 9 September: 'I have learnt so much and made huge progress in my work which I will take the opportunity of showing to certain people in Paris on my way to London' (TGA 773.9). The success of his summer's work secured Wood's solo exhibition in Paris in the following May at the Galerie Bernheim. Boat in Harbour

was amongst those shown. The painter placed great importance on this Parisian début and was aware that it could make his reputation. However, he became worried about whether he had enough work to fill the gallery, and he generously suggested that it should be shared with Ben Nicholson. In his letter to Bernheim of 16 March, written in awkwardly formal French, he explained his thinking:

In relation to my exhibition at your gallery of 15-30 May 1930, to which I look forward with great impatience and for which I will have some beautiful canvases - I think that I will not have sufficient really to fill your two immense rooms, not having large canvases like Max Ernst, for instance, and I would much prefer to exhibit twenty-five or thirty select pieces.

This is what I would like to propose to you. Ben Nicholson, a friend of mine and the painter whom I admire the most in England among the young and who has in his work the same character as in mine, will be ready to exhibit twenty-five canvases in your gallery. He is well known to your London friends the Lefevre Galleries, and Mr Macdonald, who has given Nicholson two exhibitions, will give you all the information about his painting. I propose that he has this exhibition at the same time as me, that he takes one room and I the other, in that way you would have more variety and a greater chance of selling well. He is well known in England, being the most inventive painter with great sensibility combined with an exquisite colouring. You could put on the catalogue 'Exhibition of Two English Painters' for example.

(16 March 1930, tr., Kettle's Yard Archive, University of Cambridge.)

The dealer acquiesced in this plan. Wood's work was well received, interest being shown particularly by the English collector and prospective dealer Lucy Carrington Wertheim. According to Wood's letter to his mother of 13 May, Wertheim already had 'a lot of my pictures' and had come from London to see the exhibition. There she was responsible for the majority of the eleven sales made. She subsequently reported to the Tate Gallery that Boat in Harbour, 'was purchased by myself from the artist in the summer of 1930. It hung in the place of honour at the Georges Bernheim Exhibition in the spring of that year (May?)' (8 April 1962, TG records). Sales were restricted primarily as a result of the Wall Street Crash of October 1929 which, as Wood's letters indicate, had hit his fashionable friends, and shaken the confidence of those not directly affected. Wertheim's interest was, therefore, of significance not only because the painter was continually in need of such support but also because it came at a time when support was increasingly unlikely from any other quarter. It should be noted that after the painter's death that summer, Ben Nicholson drew up a list of 'some of Kit's good ptgs' many of which had featured in their joint exhibition; from its size Boat in Harbour

is likely to be 'a large ptg (the largest in Paris show) not sold' (letter to H.S. Ede, ?Aug./Sept. 1930, Kettle's Yard Archive, University of Cambridge).

On the strength of her purchases and her continued interest in the artist and his work, Wertheim proposed to become Wood's London dealer and to open a new gallery with an exhibition of his work. It was for this show that he worked so feverishly during the following summer spent at Treboul. By her own account, Wertheim found that there was a perceptible change in style between the two seasons of work in Treboul: 'I had got so used to the sombre depth and colouring of the paintings I now owned by him - "The Yellow Man," "The Yellow Horse," "Purple Crocus," "Dieppe," "Boat in Harbour," etc., that this new mood in which he was painting came to me as something of a shock' (Wertheim 1947, p.17).

Although she warmed to subsequent works, it was the 1929 paintings that formed the basis of her enthusiasm. As a result of their close working relationship, Wertheim built a choice collection of Wood's late paintings which she retained for many years; the inscription 'BAKEWELL' on the stretcher of Boat in Harbour

probably refers to one of her Derbyshire homes. The painting is also visible in an undated installation photograph of her London gallery (Wertheim 1947, pl.XL). In the correspondence associated with her gift of the painting to the Tate, she drew attention to Evening, Brittany

(Newton 1938, no.360, present whereabout unknown) and The Crab Boat, Brittany

(ibid., no.361, Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne; repr. in col., Look here upon this picture ... and on this ... , exh. cat., Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne, Oct. 1989 - April 1990, p.24, no.84), which she had, 'always called "pendents" to the Boat in Harbour' (8 April 1962, Tate Gallery records). As the term suggests, these works are smaller but closely associated in subject and detail. The Crab Boat, Brittany

(also known as Treboul, French Crab Boat) shows a very similar boat with red sails setting to sea between bonneted women in the foreground and a port behind. In particular, the washy handling of the inky blue sea is very close to that in Boat in Harbour. Having said this, there is no indication that the relationship between the paintings suggested by the collector was one specified by the artist.

The strength of the works from the last eighteen months of Wood's life secured his posthumous reputation. A reviewer of the New Burlington Galleries exhibition of complete works could write of his 'seaside subjects': 'Without being too obviously incapable of being idealized, these scenes had a certain uncompromising strangeness which Wood knew very well how to capture' (Times, 9 March 1938). A decade later, David Baxandall was measured in his assessment of Boat in Harbour:

In a good mature painting by Christopher Wood this poetry is lasting, because it is not merely a poetry of subject. The poetry is in the paint, in the colours and the forms of the picture. Wood's gift as a colourist is very marked. ... The dark intensity of colour in such paintings as Evening, Brittany and French Crab-boat, Treboul, is equally personal and impressive. It is clear also that many of these paintings, so lyrical and immediate in their effect, have highly organised designs of great ability ... When these gifts of noble design, subtle and unusual colour harmony, and lyrical poetry are fused in works such as Boat in Harbour, Brittany

... it does not seem an exaggeration to describe the result as a masterpiece.

(Introduction, Paintings by Christopher Wood, exh. cat., Manchester City Art Gallery, 1948.)

Provenance:

Purchased from the artist by Mrs Wertheim through the Galerie Georges Bernheim, Paris 1930

Exhibited:

Christopher Wood, Ben Nicholson: Deux peintres anglais, Galerie Georges Bernheim, Paris, May 1930 (catalogue not traced)

Opening Group Exhibition, Wertheim Gallery, Nov. 1930 (catalogue not traced)

Paintings by the Late Christopher Wood, Wertheim Gallery, Feb. 1931 (17)

Christopher Wood, Wertheim Gallery, Oct. 1935 (catalogue not traced)

Modern English Painting, Libraries, Museum and Art Gallery, Altrincham, 1936 (5)

Christopher Wood: Exhibition of Complete Works, New Burlington Galleries, March-April, 1938 (106)

World's Fair, New York and tour, 1939-45 (148, repr.)

Paintings by Christopher Wood (1901-1930) , Manchester City Art Gallery, March-April 1948 (14)

The Private Collector: Pictures and Sculpture Belonging to Members of the Contemporary Art Society, Tate Gallery, March-April 1950 (299, repr.)

British Painting 1925-50: First Anthology, AC and Manchester City Art Gallery 1951 (108)

10 English Painters 1925-1955, Scottish Committee of AC, Edinburgh, Jan.-Feb. 1956 (78)

Christopher Wood: The First Retrospective, Redfern Gallery, April-May 1959 (58)

Christopher Wood Paintings, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, June-July 1966 (11)

Christopher Wood and Alfred Wallis from the Wertheim Collection, Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne, Jan.-Feb. 1968 (40)

Extended loan, National Martime Museum, Oct. 1983 - March 1985

Adventure in Art: Modern British Art under the Patronage of Lucy Wertheim, Salford Art Gallery, Dec. 1991 - Jan. 1992, Towner Art Gallery, Eastbourne, April - June 1992, Wakefield Art Gallery, June - Aug. 1992 (**)

Christopher Wood: A Painter between Two Cornwalls, Tate Gallery St Ives, Nov. 1996 - April. 1997, Musée des beaux arts, Quimper, May - Aug. 1997 (11, repr. in col. p.35)

Literature:

Newton 1938, p.73 no.359, repr. p.27 (col.)

Lucy Wertheim, Adventure in Art, 1947, pp.13, 17 and repr. facing p.39 (col.)

C, F & B II 1965, p.779, repr. pl.X (col.)

Dennis Farr, English Art 1870-1940, 1978, p.267

Virginia Button, 'The Aesthetic of Decline: English Neo-Romanticism c.1935-1956', unpublished thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 1991, p.200, repr. fig.146

Michael Tooby, Tate Gallery St Ives: An Illustrated Companion, 1993, repr. p.23 (col.)

A[ndré] C[ariou], 'Boat in Harbour, Brittany', Christopher Wood: A Painter between Two Cornwalls, exh. cat. Tate Gallery St Ives, Musée des beaux arts, Quimper, 1996 pp.34-5, repr. (col)

Also reproduced:

Sir Kenneth Clark, 'Art at the Fair: Great Britain', Art News, New York, vol.37, no.35, 27 May 1939, p.15

Eric Newton, Christopher Wood, 1959, p.35, pl.6 (col.)

Sir John Rothenstein, 'The Tate Gallery', Ambassador, no.11, 1962, p.54

Matthew Gale

August 1996

Explore

- architecture(30,960)

-

- townscapes / man-made features(21,603)

- cities, towns, villages (non-UK)(13,323)

-

- Tréboul(2)

- France(3,508)

- dress: nations/regions(272)

-

- Brittany(9)

- boat, fishing(337)

- boat, rowing(688)

- boat, sailing(3,533)

- agriculture and fishing(1,275)

- sailor(121)

You might like

-

Bertram Nicholls Drying the Sails

1920 -

Christopher Wood Church at Tréboul

1930 -

Henry Lamb Lytton Strachey

1914 -

Alfred Wallis The Blue Ship

?c.1934 -

Christopher Wood Douarnenez, Brittany

1930 -

Alfred Wallis String of Boats

c.1928 -

Alfred Wallis Two Boats

c.1928 -

Edward Reginald Frampton Brittany: 1914

c.1920 -

Sir William Nicholson Harbour in Snow, La Rochelle

1938 -

Christopher Wood A Fishing Boat in Dieppe Harbour

1929 -

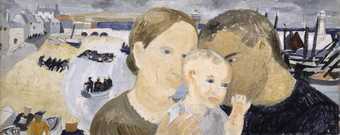

Christopher Wood The Fisherman’s Farewell

1928 -

Christopher Wood Zebra and Parachute

1930 -

John A. Park Snow in the Harbour of St Ives

1940 -

Christopher Wood Porthmeor Beach, St Ives

1928 -

Christopher Wood Untitled (Helford)

c.1926