In Tate Britain

Prints and Drawings Room

View by appointment- Artist

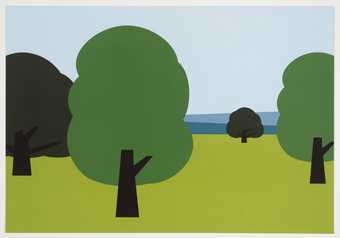

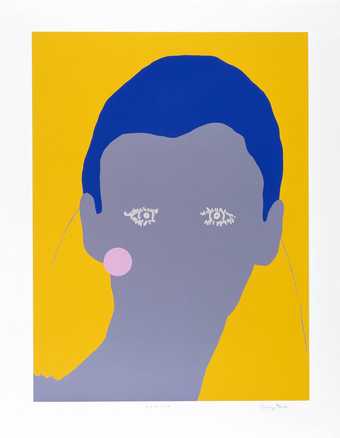

- Julian Opie born 1958

- Medium

- Screenprint on paper

- Dimensions

- Image: 610 × 529 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1999

- Reference

- P78315

Summary

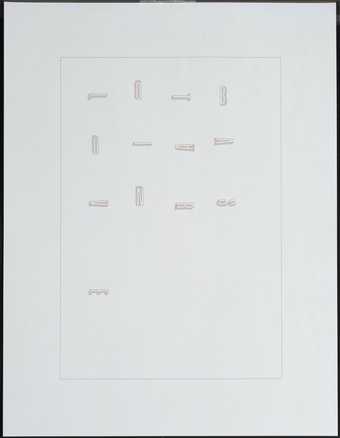

Gary, popstar is one of a series of six screenprints Opie produced in 1998-9. The series was printed by Advanced Graphics, London and published by Alan Cristea Gallery, London, in an edition of forty plus ten artist’s proofs. Tate’s version is number four in the edition. Other individual prints in the series are Imagine you are walking (Tate P78310), Imagine you are driving (Tate P78311), Landscape? (Tate P78312), Cars? (Tate P78313) and Cityscape? (Tate P78314). The prints were made from hand-cut stencils based on photographs that Opie altered on a computer. He began making portraits derived from photographs of real individuals, pared down to a series of lines and blocks of colour, in 1997. In the black and white versions, to which Gary, popstar belongs, the image is composed of lines and areas of black and white with no grey tones.

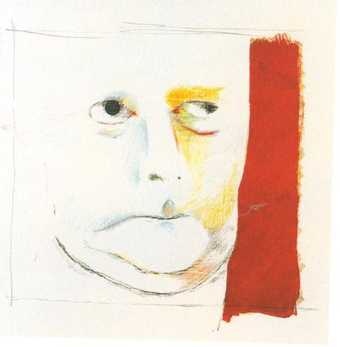

‘Gary, popstar’ is a figure Opie has portrayed in several versions. In 1998 a series of Garys was created in colour in four different sizes, small, medium, large and extra large. The two smaller sizes are c-type prints on paper mounted on wood; the two larger versions are vinyl on wooden stretchers. Gary, popstar 1998 is the same Gary depicted in black and white in the screenprint in three colours – black (lines, hair and t-shirt), flesh and green (background). Gary, popstar (with beads) 1999 is recognisably the same character, the main difference being longer, dishevelled hair. In this version he wears a pink t-shirt and a necklace of multi-coloured beads, set against a light green background. Gary, popstar (with beads and shades) 1999 and Gary, popstar (with beads shades and jacket) 1999 continue the progression with different coloured clothes and backgrounds, although beads, hair and skin remain the same. The black and white version of Gary, popstar is also available as a huge poster, advertised as ‘one day installation / easily removable / to be glued in strips to wall’ (Julian Opie: Sculptures Films Paintings, pp.26-7). Two of the versions of Gary described above are also available, in black and white, in this format. Furthermore, ‘All portraits are available as blinking films on CD’ (Julian Opie: Sculptures Films Paintings, p.29).

Pop is an important element in Opie’s work. Cartoon and comic-book imagery were brought into the realm of high art by American Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein (1923-97). Standardised or industrialised portraiture (involving different coloured versions of the same image) was pioneered by another American Pop artist, Andy Warhol (1928-87), in the 1960s in his screenprint portraits of stars. At the same time, British Pop artist Patrick Caulfield (born 1936) began painting objects as blocks of pure colour outlined in black. Opie’s most famous portraits are of the four members of the pop group ‘Blur’, Damon Albarn, Dave Rowntree, Alex James and Graham Coxon. They were used for the cover of the album blur: the best of (released 2000) and appeared world-wide on billboards, posters, mugs, t-shirts and compact discs. The commercialisation of these images and their simultaneous qualification as high art has made visible a contemporary intersection between artistic expression and the commodification of the advertising industry.

Opie has emphasised this aspect of his work by presenting it in catalogues in the form of sales brochures which illustrate and list variable formats and prices for a range of sculptures and prints produced in multiple versions and combinations. By applying this process of commercial commodification to his work, Opie would seem to be aiming to please the viewer and cater for all possible tastes. He has said ‘I think my work is about trying to be happy ... I want the world to seem like the kind of place you’d want to escape into.’ (Quoted in Julian Opie 2001, pp.4 and 8.) In the realm of portraiture, additional questions around the minimum essential information required for an image to portray a character are raised. The portraits’ titles usually consist of a first name coupled with one word stating the character’s profession or occupation. This suggests that Opie is investigating labels, both visual and verbal, questioning the nature of the information they are able to convey, how much ‘human truth’ they can reveal or fail to reveal and just what is left for the viewer to fill in for him or herself. The dehumanising effects of extreme digital simplification on the human face are evident from the blank, inexpressive appearance of the portraits.

This is Opie’s first incursion into the medium of traditional printmaking.

Further reading:

Julian Opie, exhibition catalogue, Ikon Gallery, Birmingham 2001

Julian Opie, exhibition catalogue, Alan Cristea Gallery, London 2000, pp.4-18, reproduced pp.14-15

Julian Opie: Sculptures Films Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Lisson Gallery, London 2001, pp.20-31, reproduced p.26

Elizabeth Manchester

September 2002

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- leisure and pastimes(3,435)

-

- music and entertainment(2,331)

-

- music, pop(60)

- beard(206)

- head / face(2,497)

You might like

-

Sir Sidney Nolan Landscape - Bearded Man

1973 -

Julian Opie Imagine you are walking

1998–9 -

Julian Opie Landscape?

1998–9 -

Julian Opie Cars?

1998–9 -

Julian Opie Cityscape?

1998–9 -

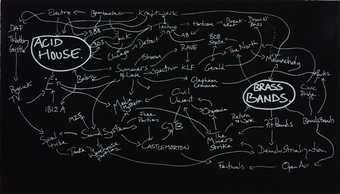

Jeremy Deller The History of the World

1998 -

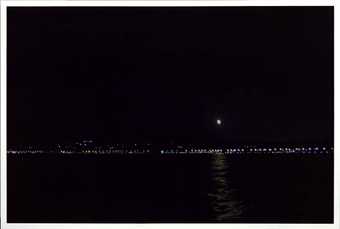

Julian Opie Distant Music Water Traffic

2000 -

Julian Opie Siren Radio Traffic

2000 -

Julian Opie Cowbells Tractor Silence

2000 -

Julian Opie Rain Voices Surf

2000 -

Julian Opie Rain Footsteps Siren

2000 -

Julian Opie Truck Birds Wind

2000 -

Gary Hume Cerith

1998 -

Richard Wright Untitled Figure 5

2002 -

Richard Hamilton Hugh Gaitskell as a Famous Monster of Filmland (1963)

1982