Not on display

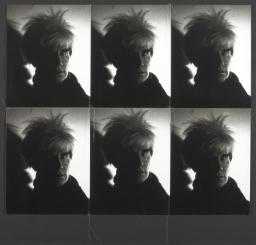

- Artist

- Richard Avedon 1923–2004

- Medium

- 3 photographs, gelatin silver print on paper

- Dimensions

- Frame: 348 × 912 × 35 mm

support: 202 × 768 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax from the Estate of Barbara Lloyd and allocated to Tate 2009

- Reference

- P13101

Summary

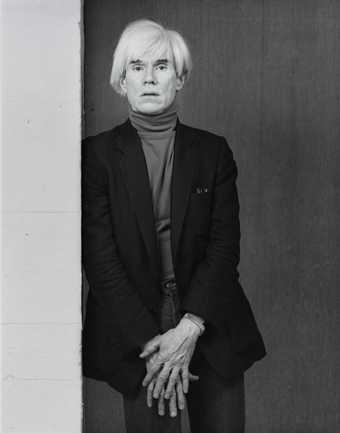

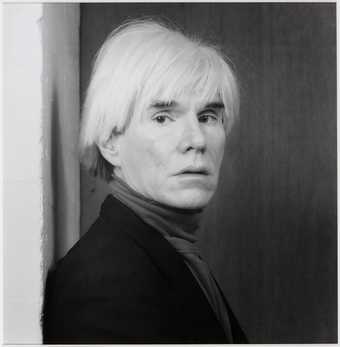

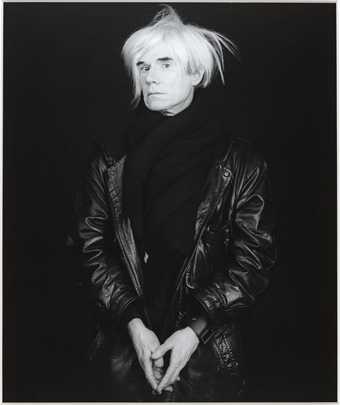

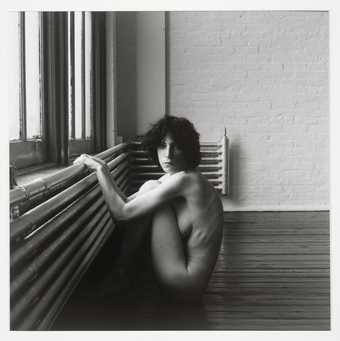

In 1969 Richard Avedon photographed the artist Andy Warhol and his entourage of aspiring actors and directors, testifying to ‘the dubious glory of the whole disreputable crew’ (Hamburger Kunsthalle 1999, p.287). Full frontal nudity, together with the inclusion of Candy Darling (a transsexual who appeared in Warhol’s films), signifies sexual daring and communicates the liberal and rebellious attitudes of the group. Warhol’s studio space, dubbed The Factory, drew the outrageous, the talented and the unconventional through its doors, and by the late 1960s had become ‘both site and symbol of the alternative culture’s disdain for the bourgeois ethic, from work to sex to control of consciousness – a sanctified space where leisure and pleasure reigned’ (Sally Banes, Greenwich Village 1963, Durham 1993, p.36).

In this photograph Avedon extracts Warhol and his disciples from their familiar Factory surroundings, and photographs them within his own studio. Avedon favoured this neutral setting, stating ‘I always prefer to work in the studio. It isolates people from their environment. They become in a sense … symbolic of themselves’ (quoted in Susan Sontag, On Photography, New York 1977, p.187). Frontally posed in various states of undress and illuminated by flat, even studio lighting, Avedon shoots the group against a plain white background. At once a group portrait and a series of thirteen individual portraits, each figure is presented in unremitting detail. Tightly cropped, their bodies fill the picture frame, with all extraneous elements stripped away. The austere and confrontational style of Avedon’s black and white image generates a clinical, psychological atmosphere. With little to hide behind, attention falls on the bodies themselves, their gestures, expressions and interactions.

Using a large format 8 x 10 inch camera and tripod, Avedon stood beside his camera and communicated directly with his sitters, fascinated by how they posed before the lens:

A photographic portrait is a picture of someone who knows he’s being photographed. What he does with this knowledge is as much a part of the photograph as what he’s wearing or how he looks. He’s implicated in what’s happening, and he has a certain real power over the result. We all perform. It’s what we do for each other all the time, deliberately or unintentionally. It’s a way of telling about ourselves in the hope of being recognised as what we’d like to be.

(Quoted in Photographs: George Eastman House, New York 1999, p.712).

Overwhelmingly, the portrait is characterised by a sense of emotional neutrality. Adopting Warhol’s characteristically affectless manner, little expression registers on the swathe of blank faces as they ‘perform’ in front of Avedon’s camera.

Rather than confining the group to a single photographic frame, Avedon breaks up the figures into small clusters and scatters them across three laterally adjoining images. The multi-frame composition evokes the sequential panels of a classical frieze or a ‘tour de force cycle laid out flat, as if the figures progressing around the belly of a Greek vase had paused for the photographer’s camera’. This reference to classical antiquity is further suggested by the ‘satiric charade of the three male (as opposed to female) graces’ enacted by the three male nudes in the central panel, and a subtle ‘play of hands owing much to Renaissance painting’ (Morris Hambourg and Fineman 2002, unpaginated).

The arrangement of bodies and casually abandoned clothes suggests an improvised and spontaneous image that reflects the louche world of Warhol’s Factory. Closer inspection reveals figures that recur: actor Joe Dallesandro appears naked on the left-hand panel and re-appears fully clothed next to Warhol on the right; film director Paul Morrissey also materialises twice, exposing Avedon’s image to be a meticulously staged tableau. The recurrence of Dallesandro and Morrissey implies a lapse in time, and promises a developing narrative embedded within the triptych. This cinematic quality is underscored by Avedon’s printing technique: by using the full, uncropped negative, each image is surrounded by the black border of the negative carrier in the final print, calling to mind successive frames in a film strip. Ultimately, the viewer is excluded from any final denouement: Avedon rejected a fourth concluding frame in which Warhol appears to video-tape Dallesandro lying in a post-coital state.

Further reading

Richard Avedon and Doon Arbus, The Sixties, London 1999.

Andy Warhol: Photography, exhibition catalogue, Hamburger Kunstalle 1999.

Maria Morris Hambourg and Mia Fineman, ‘Avedon’s Endgame’ in Richard Avedon Portraits, exhibition catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 2003.

Sabina Jaskot-Gill

April 2012

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- photographic(4,673)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- clothing(158)

- group(4,227)

- Candy Darling(1)

- Dallesandro, Joe(9)

- Emerson, Eric(1)

- Hompertz, Tom(1)

- Johnson, Jay(1)

- Malanga, Gerard(1)

- Mead, Taylor(1)

- Morrissey, Paul(1)

- Polk, Brigid(2)

- Viva(4)

- Warhol, Andy(51)

- USA(622)

- sex and relationships(833)

-

- transvestism(29)

- arts and entertainment(7,210)

-

- artist, multi-media(393)

You might like

-

Robert Mapplethorpe Self Portrait

1980, printed 1999 -

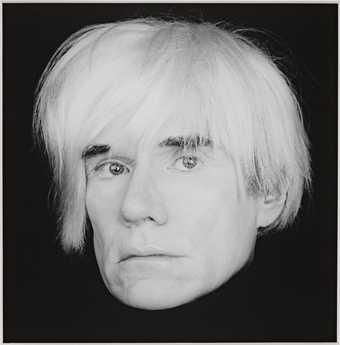

Robert Mapplethorpe Andy Warhol

1986 -

Robert Mapplethorpe Andy Warhol

1983 -

Robert Mapplethorpe Andy Warhol

1983, printed 1990 -

Robert Mapplethorpe Andy Warhol

1986, printed 1990 -

Andy Warhol Self-Portrait

1976–86 -

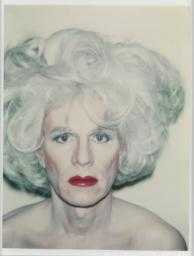

Andy Warhol Self-Portrait with Platinum Bouffant Wig

1981 -

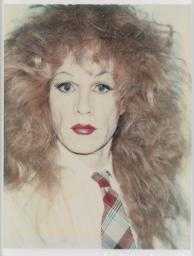

Andy Warhol Self-Portrait with Reddish Blonde Wig

1981 -

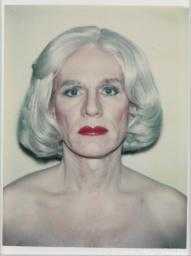

Andy Warhol Self-Portrait with Platinum Pageboy Wig

1981 -

Robert Mapplethorpe Patti Smith

1976 -

Minoru Hirata Hi Red Center’s Dropping Event at Ikenobo Hall, Tokyo, October 10, 1964

1964, printed 2011 -

Minoru Hirata Hi Red Center’s Dropping Event at Ikenobo Hall, Tokyo, October 10, 1964

1964, printed 2011 -

Minoru Hirata Hi Red Center’s Dropping Event at Ikenobo Hall, Tokyo, October 10, 1964

1964, printed 2011 -

Minoru Hirata Hi Red Center’s Dropping Event at Ikenobo Hall, Tokyo, October 10, 1964

1964, printed 2011 -

Minoru Hirata Hi Red Center’s Dropping Event at Ikenobo Hall, Tokyo, October 10, 1964

1964, printed 2011